This article is a reminder of why the mindful use of historical placenames matters.

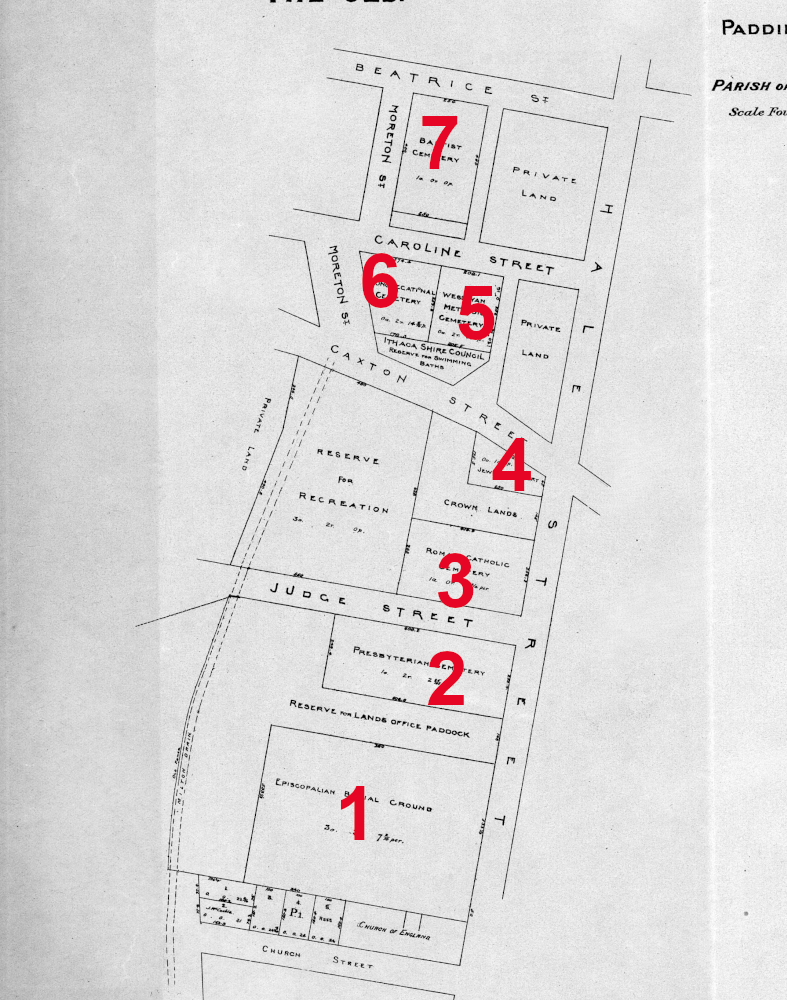

The former convict settlement of Brisbane became a free town in 1842, and during the following year two burial ground reserves were set aside there. The one in South Brisbane was a rectangular five-acre block split into seven separate denominational sections, named as Episcopalian (Church of England); Independent (Congregationalist); Jewish; Presbyterian; Roman Catholic; Wesleyan; and Aboriginal. No trustees were ever appointed to manage this reserve, and it appears to have never been used.

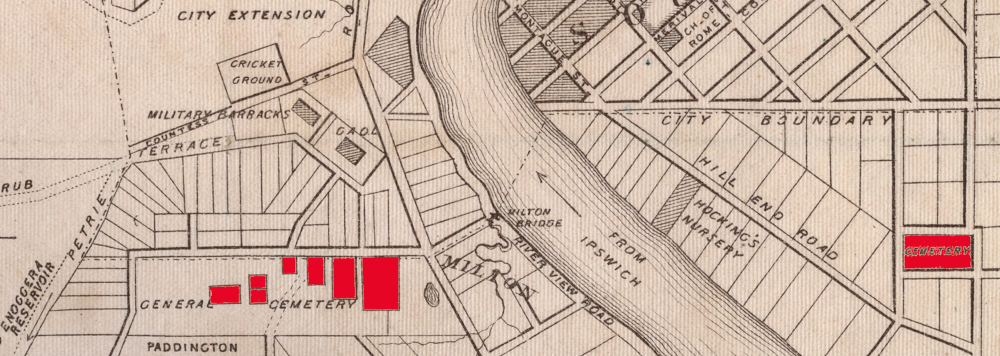

It was a different story on the northside. A reserve in what is now Milton also held seven sections allocated to the same denominations, and of a similar size to those on the southside, but these were spread over a 50-acre site, probably due to uneven terrain caused by creeks and hollows. Estimates of the number of people interred within there before its eventual closure in 1875 range from 5,000-10,000.

This place was variously known as the North Brisbane Cemetery or Burial Grounds, the Paddington Cemetery, or the Milton Cemetery. Recently, however, I have seen references to this cemetery as the ‘Seven North Brisbane Burial Grounds’, a name no doubt meant to reflect that the cemetery started life with seven separate sections and closed with seven.

I think it is important to avoid the use of this numerical nomenclature. Why? Because changes inside the cemetery reserve over time meant that there were actually EIGHT separate burial grounds at the site during 1843-75. The one that the ‘Seven’ name would exclude is the one that was no longer there when the reserve closed in 1875 – the Aboriginal burial ground, which was closed around 1862, around the time that a new Baptist section opened. The story behind the original existence of that burial ground and its subsequent closure is emblematic of early First Nations/European history in Meanjin/Brisbane.

The allocation of cemetery space reflects changing local demographics. In 1843 the dominant religious communities of Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians were granted an acre each in the north and south Brisbane reserves, while the Jewish, Congregationalists, Wesleyans and First Nations people received half an acre each.

First Nations people being given the same amount of space as these other communities demonstrates their strong presence in the local population in the 1840s. Having said that, burial within cemeteries was not standard practice within their culture (there were of course many different funerary practices across the First Nations of Australia, and that is another subject for another day).

I do not know how many times the ‘Aboriginal burial ground’ was used, and the historical use of that place would make an interesting research subject. There would certainly have been a lack of marked graves in that section, as headstones were an alien concept for First Nations people, and also rather expensive to provide. They received no obituaries or funeral reports in the press of the day, although some of those executed in Brisbane during the 1850s were sometimes described as being buried in the ‘bush’ outside the cemetery fences. This probably means the unconsecrated ground between the sections – but could it also refer to the Aboriginal burial ground itself?

The experience of First Nations people laid to rest the new South Brisbane Cemetery that opened in 1870 suggests that this anonymous funerary treatment continued for a few more decades at least. They were interred in ‘public graves’, which were used for people who could not afford a private grave plot, or who had no family or friends on hand to organise the purchase of one. These public graves had no markers, and deceased First Nations people were usually entered in the late-19th-century cemetery register under a single Anglo moniker such as ‘Billy’ or ‘Mary’. However, it is at least possible to trace the graves of these people.

The denominational divisions in the cemetery changed in the early 1860s as local demographics evolved. The late historian Rod Fisher suggested that the ‘dwindling number’ of First Nations people in Brisbane by the 1860s ‘cannot have warranted a separate cemetery’. This would appear to be a reasonable deduction, as the Aboriginal burial section was closed and absorbed into the extended Church of England grounds around 1862. A new Baptist section was added to the north of the reserve at this time, and the Presbyterian grounds were also expanded. This is an example of how changing demographics affect burial space allocation, as a major contingent of Presbyterians had arrived in Queensland in the late 1840s as part of John Dunmore Lang’s immigration scheme. Similarly, Baptists first arrived in Brisbane about 1851 and their first local church was built in 1859. The Primitive Methodists also applied for their own burial section at this time, but this request was refused and a new general section for all denominations was approved instead, although that addition never eventuated.

So these changes were all symptomatic of the displacement of local First Nations people from their country, and the concurrent growth of the European immigrant population. As we have seen, the Aboriginal section existed as one of EIGHT different burial grounds at the North Brisbane reserve during 1843-73. Any insistence on retroactively renaming that reserve as the ‘SEVEN North Brisbane Burial Grounds’ only serves to erase another piece of local First Nations history.

In History, place names matter.

Some more reading:

‘A Lang Park mystery: Analysis of remains from a 19th century burial in Brisbane, Queensland.’ M Haslam, J Prangnell, L Kirkwood, A McKeough, A Murphy, TH Loy. Australian Archaeology, no. 56, 2003.

Rod Fisher, ‘That controversial cemetery: The North Brisbane burial grounds 1843-75 and beyond.’ In R Fisher and B Shaw (eds) Brisbane: Cemeteries as Sources. Brisbane History Group Papers no. 13, 1994, pp. 35-52.