We’ve all seen them somewhere before, although most of us would not have given them a second thought. Weird, curly, slightly alien leaves carved in stone on the borders of headstones, atop classical columns, and adorning the edges of friezes. You don’t realise how ubiquitous the Acanthus mollis is in architecture until you start looking for it, then you can’t stop seeing it.

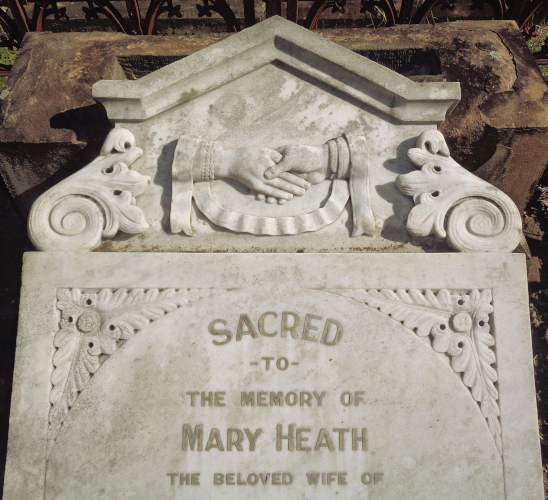

I first became aware of this plant during field surveys of cemetery symbols. Acanthus was rarely a featured motif on 19th-century headstones in its own right, unlike for example the rose and the lily, but it was used as peripheral decoration on a surprisingly large number of them. I have yet to see an example that includes the flowers.

A selection of acanthus motifs to be found in the South Brisbane Cemetery are shown below. Usage varies from primary symbol to secondary ornamentation, with leaves being closed or open, and natural or stylised. As seen here, when closed acanthus leaves are carved as a stand-alone sculpture, they can look unsettlingly like the eggs from Alien!

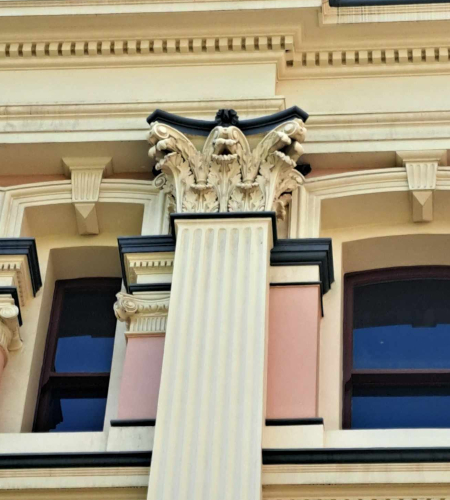

Then, during my subsequent wanderings around the Brisbane city centre, I began to notice the acanthus being used frequently elsewhere. Look up and there they are, on old city buildings, facades, columns and monuments. Their use is often discrete, but once you know what to look for, you really do start to see it everywhere.

So why is the acanthus such a common architectural feature? To begin with, a lot of Victorian-era Western architectural design was inspired by the Neo-classical movement which had developed during the 18th century and took inspiration from the symmetrical and simple forms of classical antiquity, particularly the Greeks and Romans. Advocates of this style had quite a secular philosophy and were seen by opponents as being ‘radicals and liberals’, although over time the movement became linked with Protestantism.1

Columns were a prominent feature of the Neo-classical style, and the acanthus was often used as decoration for the tops (capitals) of these columns as it had an association with ancient Greece. It was native to the eastern and central Mediterranean, where its use as an ornamental design originated. The acanthus became one of the oldest cemetery symbols as this hardy plant could be found on the rocky ground where most ancient Greek burial grounds were located.2

In Victorian-era cemeteries, Neo-classicist markers included broken columns and symbols such as urns, willow trees, mourning women, and drapes.3 The acanthus found a home on headstones because Christians had a tendency to appropriate older pagan symbols and give them new meanings, and so it was with the acanthus, whose scalloped leaves came to represent the heavenly garden. Attributing religious meanings to random objects led us down the path where acanthus thorns symbolised ‘a difficult problem that has been solved’, specifically the struggle of the spiritual journey to heaven. Going even further, some folklore traditions claim that whoever wears the leaves or has them decorating their grave monument has overcome the sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

‘Thus talking hand in hand alone they pass’d

On to thir blissful Bower; it was a place

Chos’n by the sovran Planter, when he fram’d

All things to mans delightful use; the roofe

Of thickest covert was inwoven shade

Laurel and Mirtle, and what higher grew

Of firm and fragrant leaf; on either side

Acanthus, and each odorous bushie shrub‘

– Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Excerpt from Paradise Lost: Book 4 (1674 version), by John Milton

Another factor in the widespread use of acanthus must be its versatility, with a wide variety of styles to employ, and the visual complexity of the leaves adding a touch of depth and intricacy to the carvings. As seen on Corinthian capitals, this can be a quite grand effect.

All this is why the acanthus became so ubiquitous in 19th-century Western funerary and civic architectural design. So the next time you’re in an old cemetery or the streets of a city, have a look around or up and see if you can spot its curly ancient leaves.

Footnotes

- These ‘opponents’ were advocates of the ‘Gothic Revival’ which emerged in the 1740s and was influenced by medieval architectural forms such as arches, steep gables and heavy decoration with a religious element. Its proponents had a generally conservative outlook and associated more with Catholicism. ↩︎

- The plant was introduced to Australia in the 19th century, where it is classed as a weed. ↩︎

- Obelisks were also very popular at this time, as you will notice in most old cemeteries, but they had classical roots in Ancient Egypt, which is a story for another day. ↩︎