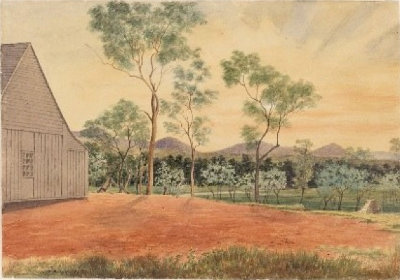

Above: Goodna Hospital for the Insane (formerly Woogaroo Asylum), 1919. (State Library of Qld)

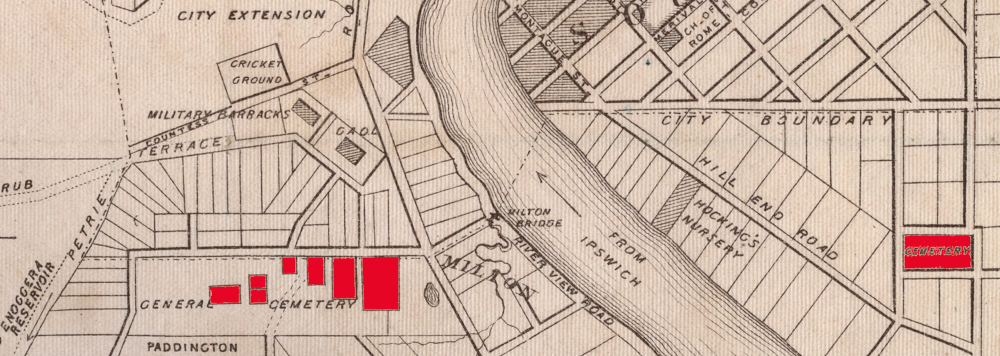

This article about the ‘Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum’ was written back in 1869. The asylum was established at Goodna in 1865, which back then was an isolated site between Brisbane and Ipswich. Prior to this time, mentally-ill people in the region had been held in Brisbane Gaol.

The facility is now known as Wolston Park Hospital, and originally known as Woogaroo Asylum. You can read more about the history of the place here.

Brisbane Courier, 26 November 1869

‘THE WOOGAROO LUNATIC ASYLUM.

Perhaps the saddest and most painful scenes it is possible to witness anywhere are to be found within the walls of a madhouse, and the man or woman who could visit an institution of this kind without being affected by the sights to be seen, must possess an unenviable strength of nerve and indifference to human suffering.

Eastern travellers report that the Turks and Arabs treat the insane with marked consideration and respect under the belief that they are divinely inspired, and it is not difficult to conceive how such a belief originated amongst an ignorant, devout, and imaginative race with respect to such a mysterious, peculiar, and terrible visitation. To see a number of fellow creatures, most of whom seem to be in the possession of robust health and all their faculties with the exception of that crowning one – reason, – to listen to their strange weird talks and observe their conduct, arouses feelings of awe and dread, of pity and commiseration, of deep humility and self abasement, which are never experienced in the same force under any other circumstances. It is a painful task to witness such a scene, and very few persons ever think of undertaking it except from a sense of duty in some shape.

This, in all probability, is the chief reason why the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum was allowed to become such an accumulation of unutterable horrors before any effectual steps were taken to reform the abuses which had crept in. The only visitors were officials of one kind or other, who, as a matter of routine duty went through the form of an inspection at stated times, and hurried away as soon as possible from the disagreeable scene. The public left the management to the Government and the officials appointed by them, and were content to accept the word of these people that everything was being done which could be done for the unfortunate inmates until at last the horrible truth leaked out that nothing, absolutely nothing was being done for them except locking them up in a foul den out of sight, and leaving them there to their own fearful devices, until the place became more like a pandemonium than a habítation of human beings.

Of course it was never the deliberate intention of any Colonial Secretary or other official person that the Asylum should become such a den of horrors. Nobody was, or pretended to be, more shocked than these same officials, when the truth was at last revealed by a searching enquiry, but that miserable parsimony which was eternally be grudging any outlay or expense in connection with the institution, while hundreds of thousands of pounds were being recklessly squandered in other directions the ignorant apathy of the public and the apparent want of sufficient firmness and decision of character on the part, of those entrusted with the management, produced the result just as certainly as though it had been a carefully devised scheme from the first.

With the present Acting Surgeon Superintendent in charge, and after the public exposure which has taken place it is hardly likely that the Asylum will be allowed to again fall into such a state as it was found to be at the commencement of the present year, but the only sure mode of preventing this is, for the public to keep a vigilant watch over the institution, and make sure that it is not being neglected. The most devoted and energetic of surgeon superintendents is apt to lose heart in time if he finds himself left single handed to battle with all kinds of obstacles, and the present Government seem just as much wedded to the “penny wise and pound foolish” policy as were any of their predecessors. An over active zeal for economy by saving the ‘pickings’ is, unless checked, almost certain to result in the striking off of necessaries, where it can be done with impunity, rather than superfluities, which are likely to be resisted. The present Government, like all previous ones we have had in this colony, are exceedingly pacific, not to say pusillanimous and their action is influenced in a great measure by the probabilities of meeting with active resistance from any quarter – not by any simple rule of right. If the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum is made what it ought to be and can be made, – a clean, comfortable, and healthy retreat where the insane can be treated under the condition most favorable to their recovery – it will be because the Government are urged on to make it so by the pressure of public opinion not from any voluntary action on their part.

At present the asylum is very far from being what it ought to be and already there are symptoms of peddling make-shift expedients being advocated by the Government rather than a thorough and sweeping reform-such as is needed. We paid a visit to the asylum a few days ago for the purpose of seeing what had actually been done and what was proposed to be done for the purpose of rendering the place more endurable and a more fitting hospital for the treatment of the insane. We dropped in quite unexpectedly in the afternoon, and were received very cordially by the Acting Surgeon Superintendent, Dr Challinor, and shown over every part of the buildings and grounds. The Doctor seems to take a real pleasure in pointing out what has been done, what he intends doing, and what he hopes to be able to do in the way of improvements and reforms, and he is justified in feeling a little proud of his work so far. He, at all events appears to be the right man in the right place at Woogaroo. He has evidently entered upon his duties con amore and made the treatment and care of the insane an absorbing study, to which he brings that genuine kindness of heart singleness of aim, and persistent tenacity of purpose which rendered him such an intractable politician. He also seems to have a good first lieutenant in the present chief warder Mr Jessie, who in addition to his experience as a warder in the Melbourne Lunatic Asylum, evidently possesses the qualities of kindness decision of character, love of order, and administrative faculty, so requisite in an officer of this kind. The Doctor and Mr Jessie have already effected many and great improvements, as may be seen at once by anyone visiting the place – but having, as it were, to begin with chaos, the distance from thence to perfect order is very great, and the Government are beginning to dis cover that it is also very expensive to traverse.

They have not as yet gone the length of decidedly refusing to carry out the reforms to the desired consummation which hare been commenced, but they are not showing that alacrity which the necessities of the case require, and the public will demand. The male wards are fearfully overcrowded, and although the number of patients keeps increasing, we could not see or ascertain that any provision whatever was being made, or in contemplation for providing increased accommodation for them. The building itself was not originally intended for occupation by patients and therefore can never be made a very commodious and well arranged asylum.

Still a great deal could be done to improve the accommodation at present provided. In the first place, the over crowding could and ought to be provided against without a single day’s unnecessary delay. The building is a brick two story one, and the upper floor rooms are used as dormitories. These are in process of being made as comfort able as circumstances will permit. The ghastly white walls are being colored to a warm cheerful tint, and the patients are provided with clean sheets, pillow cases, and coverlets to their beds, in addition to the blankets, or fragments of blankets, which before time were their only bed clothing. But the beds themselves are so thickly placed, that it is difficult to walk between them. The occupant of one bed can, by merely stretching out his arm, reach over to the middle of the bed occupied by his neighbor on either side, and even in the daytime, when all the rooms were unoccupied, as they were at the time of our visit, those rooms in which the windows were closed to keep out the rain, had a close and sickly smell. When every bed is occupied, and the door closed, during a hot summer’s night, the atmosphere must be terribly oppressive and injurious to health, not to speak of comfort.

The dormitories, four on each side, if our memory serves us correctly, are divided by a narrow corridor. Each room is crowded with beds in the manner described, some containing as many as fifteen, and there is no means of separating the noisy from the quiet patients. A sane man of nervous and exciteable temperament, doomed to pass a week in such a place, would inevitably become as mad as the maddest of his fellow denizens.

The warders an no better provided for than the patients. The chief warder, his wife and family, seven in all, occupy, and are obliged to reside, in a couple of rooms at the end of a range of wooden buildings near and at right angles to the main entrance. The remainder of the building is used as doctor’s office, chief warder’s office, storeroom, &.c. By taking a portion of the storeroom, the chief Warder has been able to add a small sleeping room to his quarters, and, by close packing, he and his family can now manage to sleep in the place. But the door is close to the refractory yard on the one side, and the hospital on the other, every word uttered in these places – and the language is sometimes horrible, is heard by the chief warder’s wife and children, even when the door is closed, and there is no back yard accommodation whatever.

Another range of wooden buildings, running parallel to those already mentioned, forms the kitchen for the men, and a miserable little room at the end is made to accommodate four warders. The size of the beds and their closeness together reminds one of the ‘tween decks of an immigrant ship more than anything else, and the proximity to the kitchen, being only divided by a wooden partition, must render the room particularly lively at night with one kind of vermin or other. The rest of the warders are accommodated in the same luxurious style inside the main building. The ground floor of the main building consists of hospital day rooms for patients, warders’ day room, and dormitory for dirty patients. At present there are only eight patients required to be placed in this ward.

Under the old regime, patients were left to please themselves as to how they went to bed, and the result was that some from perversity, others from paucity of bedclothes or the like, went to bed without undressing. The majority of the patients did so, and some even carried the thing so far as to go to bed in their hats, as well as coats and boots. Now that clean sheets, pillows and pillow cases, blankets and coverlets have been provided for the beds, the doctor has had shelves put up on the corridor wall, at the entrance to each dormitory, and the patients are all obliged to undress and have their clothes placed on the shelf until morning. The poor unfortunates not only understand and duly appreciate the change, but already there is a marked alteration for the better in their habits. Cases of dirtiness are becoming less frequent, and men who would never rise to satisfy the call of nature have latterly been known, during an attack of diarrhoea, to get up four times in a single night. A few of Mr Tiffin’s self acting earth closets have been supplied to the institution on trial, and are found to answer admirably. The presence of these in the rooms no doubt has added to the gratifying result. The sooner a full supply of these for every ward is provided, the better it will be.

The old hospital, a miserable little shed quite unfitted for the purpose, has now been converted into a bath and lavatory, where a certain number of the patients are once a week provided with a very comfortable plunge bath, with ample supply of soap and water, and can get an extra swill from a shower bath to wash the soap off after. Indeed baths and lavatories have now been fitted up in every ward, and in addition to a force pump, which provides a supply of water from tho creek, a new under-ground tank has just been constructed, capable of containing 32,000 gallons, to store the rain-water from the roof of the buildings, so that an ample supply of water will be provided.

The present hospital consists of three adjoining rooms at the main entrance to the building on the left hand side, they have just been conveniently furnished with half tester iron bedsteads, which are to be provided with mosquito curtains (!) in addition to the sheets, coverlets, and other luxuries of modern date. The third room is darkened, and is appropriated to the use of the patients who are suffering from ophthalmia. The hospital might be rendered very comfortable by opening a door from the first room into the yard at the back, called No. 1 yard, which cannot be used now, and erecting a verandah over a recess in the building at the part near the door. It is doubtful whether this will be done without some pressure is brought to bear in the proper quarter, the objection being the expense. The extra space and greater comfort, however, that would be thereby provided, fully justifies the outlay, which, after all, would not be considerable.

The day rooms for the patients are at the opposite end of the building to the main entrance, and open into a yard called No 2 yard. Originally this was a small place enclosed with a tall hardwood fence, which completely shut out everything except a view of the sky above. The cross fence has been removed, and the yard extended nearly to the river, so that now the poor fellows can obtain a view of the river and a portion of the surrounding country, as well as having more space for exercise, and a much better supply of fresh air. The yard is not so complete as it might be made, as it is still only provided with the old fashioned privies, the wells of which are now full to overflowing. There are half a dozen new earth closets standing in the shed of No 1 yard, apparently for the purpose of supplying the place of these privies, but they have not been put up as yet, although they have been there some time.

To the right of the main entrance is the refractory ward and yard called No 3 yard. This yard, which used to be a mud hole in wet weather, has been gravelled and made comfortable, and on the further side a lavatory, bath, and shower-bath have been provided. The tank over the bath room is capable of containing 1400 gallons of water, and once a week the refractaries are stripped to the skin and thoroughly cleansed with soap and water in the plunge bath, and finished off in the shower bath. The latter is constructed to only discharge a very small body of water, and as the operation is performed in the afternoon the water in the tank above is generally tepid, and therefore not disagreeable. The only room in the building remaining to be mentioned is the warder’s day and dining room. A list is kept in this room of every patient in the hospital, and each warder has to enter a return on this list three times each day – morning, noon, and night, of every man under his charge.

All the rooms are kept scrupulously clean, the men are supplied with clean clothes, and the beds with clean sheets and pillow-cases once a week, and clean blankets, coverlets, and bed-ticks as frequently as occasion requires. How this is managed is a mystery that we shall not attempt to fathom, but we were assured that it was done, although the laundry is only supplied with two ten gallon coppers – the Government being such rigid economists. Mr. Hodgson, in the first burst of public indignation on the discovery of the state of the asylum, took it upon himself to order a recreation ground of about four acres in extent to be fenced in; this has been done, and an admirable improvement it is for the the men can and do make holiday here every Saturday, playing cricket, quoites and a number of games, to their evident gratification and permanent benefit. But there is no shady place for them to retire to except a temporary shelter contrived by the chief warder with some fragments of Osnaburg cloth-utterly inadequate for the purpose. And, what is worse, the laundry is within the fence, and the women employed are therefore subjected to some annoyance from the male patients when admitted to the recreation ground. The other available amusements for the patients are cards, draughts, dominoes, and bagatelle, most of which are impossible for want of sufficient room to play in without interruption. Mr Hodgson, before leaving, presented the Asylum with a very handsome and costly bagatelle board, his private property, but the Doctor is obliged to keep it packed up in his store, because there is no room in which it could be set up for play.

The kitchen for this division of the Asylum is large, and seems to possess ample accommodation for every requirement. The rations, too, are of excellent quality and ample in quantity, as the following dietary scale will show – Each patient receives daily, 1 lb fresh meat, 1 lb bread 1 lb vegetables, 1 oz rice, 1 oz salt, 1 gill milk, 1/2 oz tea, 2 ozs sugar, 2 ozs maize meal for hominy, 2 ozs mollasses, 1 oz soup, and 1 oz of butter to sick patients, or those who desire it. The weekly diet list is -Sunday, roast beef, plum pudding, soup, vegetables, and tea , Monday, corned meat, potatoes, pumpkins, or other vegetables, Tuesday, stew and roast beef, Wednesday, mutton, roast and boiled, soup and vegetables, Thursday, roast beef and vegetables and soup , Friday, mutton, roast and boiled, and vegetables , Saturday, roast beef and vegetables. All the men who work are supplied with tea each day, and half a pint of beer each daily.

The work for the men is road making, fencing, gardening, and other occupations of a similar character, and from a daily return of the chief warder, we found that out of 118 healthy patients the daily average number of workers is over 76, and of 54 women, 38 are employed in useful occupations of one kind or other. These facts speak volumes in favor of the new management. In fact, all that is now required to render the male portion of the Asylum very comfortable, and tolerably complete, are the addition of a cottage ward, capable of accommdating about forty patients, ten or eleven new cells for refractories, new quarters for the chief warder, better accommodation for the under warders , the removal of the laundry to a more convenient situation, and providing it with a bettor supply of utensils, and the erection in every ward and yard of the self acting earth closets. As yet, however, we could not learn that any of these improvements were likely to be carried out. Plans for the whole were prepared by the Colonial Architect, but when the estimates came to be sent in, some of the members of the Ministry shrank from the outlay, and thought it must be deferred until the public purse was better supplied with cash-an event which may happen in some succeeding generation, but is not at all likely to occur in this.

In the female portion of the Asylum a number of extensive improvements have been commenced, which, when completed, will leave little to be desired. Fortunately they were well begun before the Government were taken with their last fit of economy and retrenchment, so that they are in a fair way of being carried out. They will consist, in the first place, of a detached cottage ward, of wood, two stories in height, with eight feet wide verandahs round three sides and most part of the fourth. This building is being erected on an elevated site a short distance from the present female wards, and will command extensive views of the river, the village, and the surrounding country, including Mount Flinders in one direction – altogether a very pretty and pleasant site. The ground floor will consist of a day room and dormitory 24 feet by 40 feet, and the remainder of the available space, both below and above, is divided into lavatory and bath rooms, nurses’ room, sleeping rooms, and the like. Six of the sleeping rooms will be single ones, 8 feet by 9 foot 6 inches, for quiet and convalescent patients. The windows, in stead of being barred, will be made with narrow panes in frames of wrought iron, in shape and size like the ordinary wooden sashes, from which, when painted, they cannot be distinguished. this will get rid of the prison look of the place, which is now objectionable and depressing to the patients. There will be no balcony to the upper rooms, but the windows will be fitted with Venetian shutters. The whole ward is to be fenced in with a substantial fence, so as to enclose a large recreation ground of about four acres.

Another improvement which is also in a satisfactory stage of progress consists of a large and well appointed kitchen and offices. The ground floor is about equally divided. One part of the main building consisting of a kitchen 20 feet by 20 feet, to be fitted up with a Russell stove capable of cooking for eighty persons , two large boilers and other kitchen requisites. The other part, consisting of a large room also twenty feet by twenty feet, is to be a warders or nurses dining and day room. It was originally designed to have the kitchen chimney so constructed as to admit of a fireplace for this room, but, by an unwise alteration, as we think, the fireplace in the dining room is to be dispensed with. Even in Queensland, and especially by the river side, in winter, a fire in a room is absolutely necessary to render it all comfortable, and there is no reason why the nurses should not be made as comfortable as circumstances will permit.

In addition to the rooms already mentioned there will be nurses bed rooms, store room, pantry, etc. At the front of the kitchen will be a verandah eight feet wide, floored, and at the back a ten foot wide verandah, not floored. Among the minor improvements in this portion of the institution are the enlargement of the yards and the construction of covered airing courts in the refractory yard. The main yard has been opened out nearly to the river, giving a splendid view from the upper part of it, and the refractory yard has been largely extended in the opposite direction. The covered airing courts before referred to is an excellent scheme of the Doctor’s for dealing with refractories. They consist of a series of courts 7 ft 6 in wide, and about 20 ft long, covered at the top, the sides being constructed of narrow hardwood boards fixed upright, allowing small spaces between – something like an ordinary sawn wood paling fence only much higher. The boards are all nailed on from the inside, so that escape is impossible, and the inmates cannot injure either themselves or the building.

However refractory and troublesome a patient may be, all that is necessary is to put her into a strait waistcoat and lock her up in one of these courts for a few hours She is there secluded from the other patients, and at the same time has the benefit of the fresh air and such exercise as she likes to take, without the necessity of being attended by a nurse. One poor creature we saw there could never be taken out into the fresh air without two nurses to attend her until these courts were constructed. Adjoining the courts are the refractory cells, or rather they are in process of removal from their old site to the bottom end of the new refractory yard. The female ward although at present too crowded, is much better adapted for the purpose of a lunatic asylum than those occupied by the men. One half of the ground floor forms a day room or covered court, and along the sides are the sleeping rooms, capable of holding three beds comfortably, but now containing four beds each. The chief nurse’s cottage is also as crowded as the male warder’s rooms, but when the new kitchen and cottage ward are completed this objection will be removed.

Objection has been taken to the site of the asylum, but we cannot agree with the objectors in this particular. There are all the natural features requisite to render the site both healthy and pleasant, and by a re-arrangement of the fences, an extension of the yards, and other improvements of the kind, a good deal has actually been done in this direction already. The doctor appears to have been indefatigable in his efforts to effect improvements in this way, and has been eminently successful. Indeed the amount of good useful work which has been accomplished by the patients alone in the way of fencing, road making, clearing, and beautifying the grounds, during the last six or seven months, is really surprising. A great deal more is in contemplation, and will, we hope, be carried out, as it involves very little expense and finds beneficial occupation for the inmates. One of these is the construction of a wharf and approaches, partly done already, for the landing of Government stores and other requisites for the asylum from the river. Another is the laying out of a large garden, so that the inmates may grow their own vegetables. A third is beautify the grounds, and for this purpose Mr Walter Hill has not only promised to furnish designs, but also the requisite number of trees and ornamental shrubs.

A very popular innovation has been introduced in the shape of bi-weekly balls on Tuesday and Friday evenings, to which a few of the well conducted villagers are admitted, and all the patients who can attend. One of the patients, a warder, and two villagers, supply the music, the dancing is engaged in as heartily, and the enjoyment is as real and great as at the most fashionable ball in the grandest room in the colony. What is better still, it is found to have a permanently beneficial effect upon the health and spirits of the patients. Sometimes visitors drop in from Ipswich, although it is ten miles distant. Brisbane is almost out of the question, being fifteen miles away, and to attend one of the balls would necessitate staying in the village all night, and returning to town next day.

The general impression left on our mind by this visit to the Asylum is, that Dr Challinor is well qualified for the duty he has undertaken, is really and heartily desirous of conscientiously performing that duty both to the letter and spirit, and that he is well seconded by his present chief warder and chief nurse. That a wonderful change for the better has been effected in almost every direction, but that still more requires to be done in order to render the Asylum decently comfortable, and that the only way of securing this end is to keep public attention constantly directed to it.’