Above: Wolston House, undated image. (State Library of Queensland)

Wolston House, on Grindle Road, Wacol, is a heritage-listed historic home built during the 1850s and then expanded in the 1860s. In the context of non-Indigenous Queensland history, this is very early. The house now operates as a museum and tour site, managed by the National Trust of Queensland. A brief history of the place is provided on the Richlands Inala History Group website, and its listing in the Queensland Heritage Register can be seen here. In short, it is a significant place worthy of being treated with a lot of respect.

So it was with some dismay, then, that I (as a qualified historian) watched a YouTube video of an event held there. This was a ‘paranormal investigation’ run by a group called Pariah Paranormal and promoted on the National Trust website. The video can be seen here, and the section relevant to this article begins around the 7:40 minute mark.

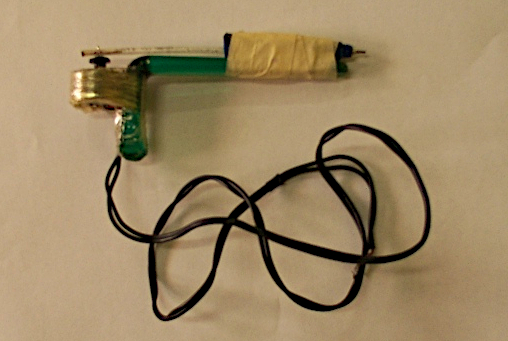

While standing in the basement of the house, the guide claims that the spirit of an Indigenous man named ‘Yemmy’ can be found there. Various ghost-hunting gadgets are placed around the room, while other attendees hold devices such as the ghost-hunting phone app ‘Necrophonic’. This ‘scientifical’ toy is available for $10 on Google Play and advertised for use in ‘spirit communication’ – detecting background sounds and translating them into what a spirit is allegedly saying.*

Misleading History

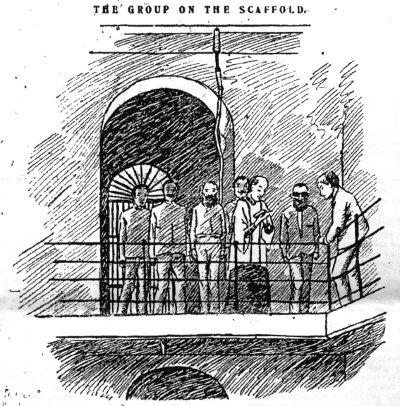

The guide tells the group about the history behind the alleged spirit of the First Nations man. He claims that Yemmy was hanged for rape in Rockhampton in the 1860s and has returned to Wolston House because he once worked there and ‘was happy here’. He then provides the details of the crime which involved various First Nations men including Yemmy and Toby.

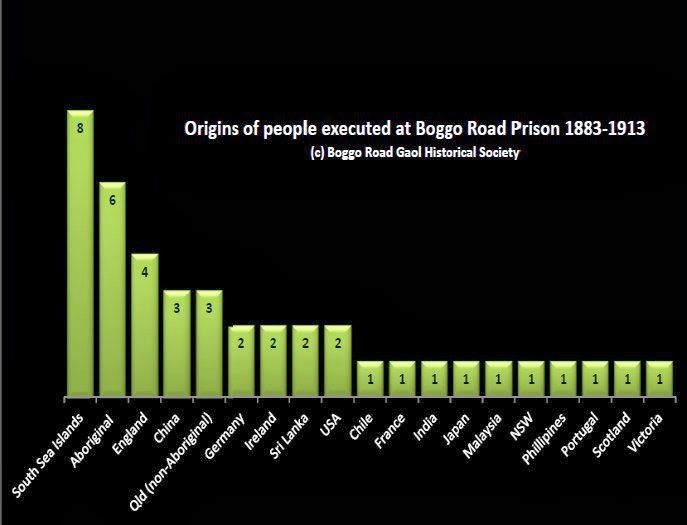

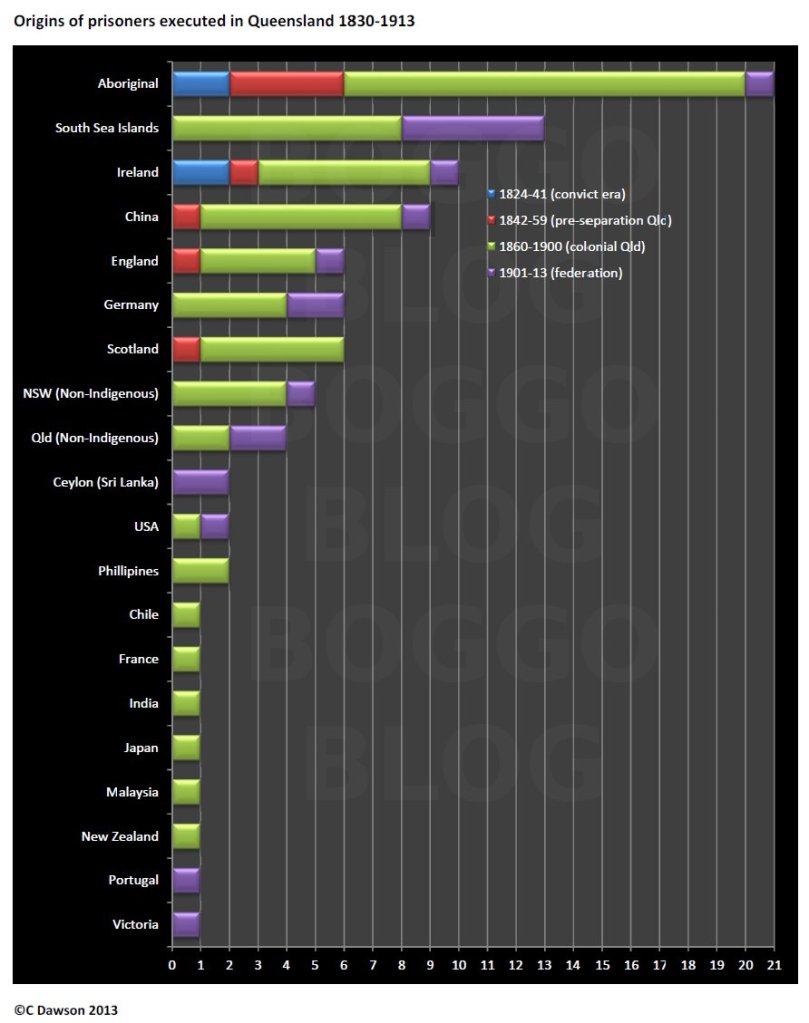

As a historian of capital punishment, this story immediately struck me as false. There were 21 First Nations people executed at Moreton Bay and Queensland during 1830-1913, and none of these were called Yemmy, Jemmy, Jimmy or Toby. The only First Nations person hanged in Rockhampton was George in 1871, and nobody in Queensland was hanged for a crime as described in the guide’s story. (See here for details on hangings in Queensland). This entire story has absolutely no basis in the historical record.

Unfortunately, unless they know better, customers on any such tour tend to believe what they are told by the guides and will have left Wolston House thinking that it is haunted by the ghost of a First Nations man hanged in Rockhampton for murder, and who likes to get drunk.

Which would be absolutely wrong.

It is crucial that the historical interpretation of heritage places is based in fact, as the significance of any such place is in part shaped by community perceptions of the associated history. Presenting Wolston as a ‘haunted house’ will lead to some customers thinking that the most significant (or even the only interesting) attribute of that place is that it is allegedly haunted. This undermines the significance and real history of the site as described in the heritage register.

Cultural Insensitivity

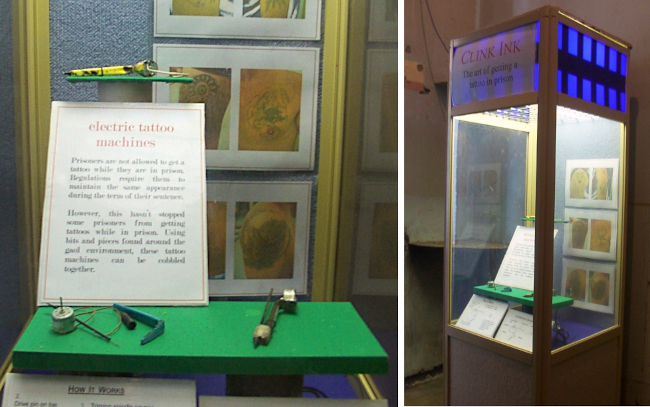

There are also serious cultural sensitivity issues for anyone claiming to be interacting with the spirits of Indigenous people, especially in a commercial setting. This is the main reason that similar paranormal ‘investigations’ were banned by the Queensland Government at Boggo Road Gaol – because customers were playing ghost hunting in cells where First Nations men had died in tragic circumstances, and within living memory.**

The Wolston House video shows how the people in the room appear to treat the encounter with ‘Yemmy’ in a light-hearted manner, often laughing at what they claim the spirit is saying to them via ‘Necrophonic’. At one point the guide encourages Yemmy to ‘drink’ some whisky from a bottle (in order to displace a flashing toy ‘cat ball’ perched on top of the bottle). He makes several references to how Yemmy likes to drink alcohol. There are constant requests for the spirit to do or say things. Almost as though it was a performing seal. ‘Do this, do that’.

Unfortunately, there are other similar videos out there too. They depict what appear to be other ghost hunting teams gaining private access to Wolston House in the company of Pariah Paranormal and entering the basement area. Once again there are constant requests for Yemmy to ‘drink’ from the bottle, make the cat toy flash, turn lights different colours, and say things (see here from 18:15 – 24.30 minute mark [also from 1:18:55]***, and here from the 2:40 mark).

If one was to accept that an Indigenous (or any other) ‘spirit’ does indeed dwell in Wolston House, the documented commodification and treatment of that spirit is clearly unacceptable.

I fully understand the pressing need to raise funds for the maintenance of Wolston House, and I used to be on the National Trust of Queensland Council. However, I believe there are alternative ways to present ‘paranormal-themed’ activities that are respectful, entertaining, ethical, historically factual, and genuinely educational. The National Trust of Queensland should be capable of sourcing alternatives.

The commercial ethics of using pseudo-scientific ‘paranormal investigations’ for heritage fundraisers can be debated, as can the need for site managers to be more innovative and original about how they raise money, but the content of these particular events is demonstrably unprofessional, culturally insensitive, and historically inaccurate. Wolston House and other old heritage sites deserve better than being treated like Scooby Doo funhouses.

Update 3 August 2022

Since I brought these incidents to their attention, the National Trust of Queensland have conducted a review of these incidents and have advised the group involved that any historical information used in their tours in future must be correct and that they no longer ‘conjure or invite any Indigenous spirits or otherwise’ (or at least pretend to). They also need to ‘ensure the integrity of Wolston Farmhouse and the brand of National Trust Queensland be respected and preserved’. The review is ongoing.

Well done to NTQ for taking this action. This obviously means the ghost hunts will need to be radically changed to satisfy these requests. This is a good thing, but it is still concerning that groups that need to be told these things are allowed anywhere near heritage places.

Notes

* Without going into depth on the subject here, there is no scientific evidence that the instruments used for ‘paranormal investigations’ actually work as advertised, and plenty to show that they do not. It could be argued that there are serious ethical concerns in advertising that these gadgets do work, and then charging customers significantly high prices to use them.

** Paranormal investigations have also been prohibited in Brisbane cemeteries by the Brisbane City Council because of obvious issues of disrespect. As it stands, Ipswich City Council and the Goodna Cemetery Trust are the only cemetery authorities in the world to permit such activities in cemeteries under their control.

*** This video is now hidden, after the group involved tried to make me remove the link. I refused to do so.