‘A ‘BOOB’ IN A BAOB TREE.

Away up in Western Australia’s wild and woolly nor-west some distance out of Wyndham there’s a boob in a baob tree which is surely the queerest gaol in the world! It was used in the early days for imprisoning natives overnight while on their way to the township for trial and it is known officially as the Hillgrove Lockup.’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1940)

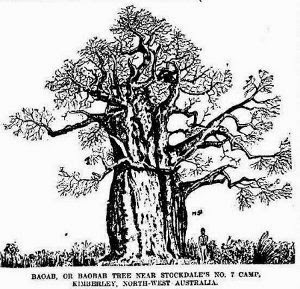

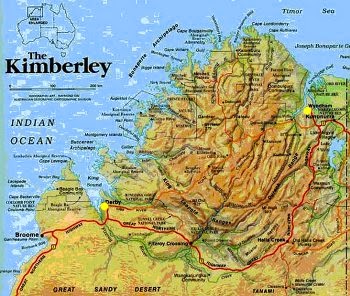

‘A Boob in a Baob Tree’, indeed. Well played, headline writer. ‘Boob’ is slang for ‘prison’ and, yes, he was writing about keeping prisoners inside a tree, specifically the rather peculiar boabs (Adansonia gregorii, also known as baobabs among many other names) found in the Kimberley region of north-western Australia.

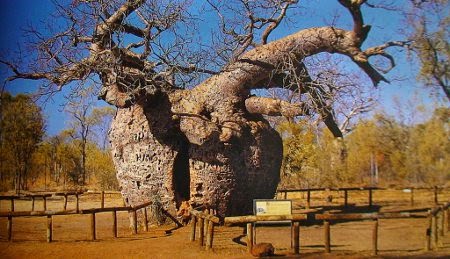

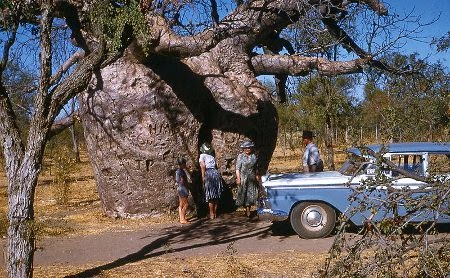

There are two such ‘prison trees’ in the Kimberley region, one near Wyndham and another near Derby, some 900km away. Plenty has been written about these trees over the last century, thousands of intrepid tourists have photographed them (they have been tourism drawcards for decades), and the trees are even listed in the State Heritage Register of Western Australia. As boabs are some of the longest-living lifeforms in Australia (some are estimated to be 1,500 years old) their future as historical icons seems assured.

However… as a historian I would say that extraordinary claims demand hard evidence. There are plenty of retrospective tales about these trees being used as lockups, but is there any decent evidence? I tried to find some…

The Story

On the King River and Kurunjie Gibb River roads just south of the small town of Wyndham stands a large hollow boab tree at least 15 meters in circumference. This is the ‘Boab Prison Tree’, widely thought to have once been used as a makeshift lockup around the turn of the 20th century. Back then it was reportedly known as the ‘Hillgrove Lockup’. It was often necessary to march prisoners in chains over hundreds of kilometres from their places of arrest, and safe overnight camping places were required where the prisoners could be secured (according to a 1905 government report, about 90% of First Nations arrests in the region were for cattle-killing).

A similar tree just south of Derby is also said to have been used to confine First Nations prisoners being transported to Derby in the 1890s. The hollow had a ‘ceiling’ about 6 metres high with two natural holes for ventilation.

Newspaper articles about these trees began to appear in the 1910s and were already referring to their use as lockups in the past tense. The earliest mention I’ve found of it so far is in a Perth newspaper of 1919, which simply featured a photo with the caption, ‘A Boab Tree at the King River Pool, Kimberley. It is known as tile “Hill Grove Lockup.” Twenty-six native prisoners have been held in this tree at one time.’

Occasional newspaper articles over the following decades repeated the claim and generally provided very similarly worded information. The story goes that patrolling policemen in the 1890s or 1900s discovered that the Wyndham tree was hollow and they cut a person-sized opening so they could use it as a lockup for First Nations prisoners they were transferring to Wyndham. This was no mean feat as the walls of the tree are about 60cm thick. The entrance was said to have been fitted with an iron grille.

The internal capacity was around 9 square metres, reasonably roomy for inside a tree but probably not enough to accommodate 26 men, as claimed in this 1923 article, or 30 prisoners as suggested in this 1931 Queenslander article. This claim of 30 was also made by Ernestine Hill in her 1940 book The Great Australian Loneliness. A 1940 article makes the more realistic claim that some prisoners were chained to the outside of the tree when the hollow was full:

‘Some years ago a trooper was bringing into Wyndham a party in chains when at dusk they arrived at the baob-tree. As there wasn’t room inside for everybody the trooper chained two of the prisoners to the tree. One of the pair was a magnificent specimen of a man well over six feet high with well shaped arms and legs and a blacksmith’s chest. At daybreak that native was missing and so was the chain. But an iron bolt to which the chain had been padlocked was left bent back in the form of a hairpin.’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August 1940)

It was also claimed in the Mirror (Perth) in 1936 that ‘the Queerest Gaol in All Australia’ had a huge bolt fastened into it for chaining prisoners to.

The boab has soft bark which allows people to carve graffiti into the tree, and a photo taken circa 1917-23 shows the words ‘Hillgrove Police Station’ cut deeply into the Wyndham tree (it can be seen here). Of course, a bit of graffiti does not prove anything – I could carve the same words into any old tree – but it does show the lockup story had currency at the time. Hundreds of other names and initials have been cut into the tree since then and the Hillgrove graffiti has all but disappeared.

Not as much was written in the newspapers about the Derby boab, and a 1966 article on boabs in that esteemed academic journal Woman’s Weekly even suggested that the Derby tree was probably never used as a lockup, although they did add the rider ‘unlike the other well-known hollow baobab at Wyndham’.

Despite this, the two trees were heritage-listed in the 1990s. It is claimed in the State Heritage Register entry (under ‘Prison Boab Tree’) that the Wyndham tree was used as a lockup, and there is also emphasis on the Indigenous significance of the tree, although all uses are part of ‘a long oral tradition history of use’.

The entry in the same register for the ‘Prison Boab Tree’ of Derby makes the more ambiguous claim that the tree was ‘believed’ to have been used as a lockup. Despite this, it is noted that the tree is significant as ‘a symbol for the town of Derby as for the history associated with it. It represents the harsh treatment prisoners often received in the north of Australia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’. It is also noted that the tree is a ‘well established tourist landmark’, but then boabs in general have attracted sightseers since the 19th century. Indeed, the popularity of the prison trees and the resulting stream of people climbing into them and carving names in the bark has resulted in the trees being fenced off.

This popularity shows no sign of diminishing. Numerous images of the trees, many taken by tourists, can now be found on the Internet, and dozens of websites feature the ‘prison tree’ claims. Some of these websites are travel blogs, others are dime-a-dozen travel advisory sites, and others (including local and state government websites) use the trees to promote local tourism. Worst of all are the ‘Amazing Top Ten’ sites that infest the Internet with unoriginal information. Look up some of the website types named above and you will instantly notice the unfortunately common practice of cutting-and-pasting entire blocks of text from one website to another. And so the legend spreads…

Behind the Stories

The fame of the Boab Prison Trees is well established in national folklore and it is easy to see why. A string of occasional newspaper articles – especially from the 1930s onwards – pretty much repeat similar stories of First Nations prisoners being confined within the boabs. Various authors mentioned the Derby boab tree elsewhere. JK Ewers wrote about the boab tree that was used ‘for a gaol’ for a 1949 edition of Walkabout magazine. In his 1961 book The Land That Sleeps, Gerald Glaskin mentioned the ‘famous’ tree having been ‘hollowed out and used as the township’s jail’. Mary Wilcocks similarly wrote of the ‘famous prison bottle tree’ in a 1966 article for Walkabout.

This repetition has been amplified a hundredfold on the Internet, but all these sources seem to contain a lot of hearsay and no direct evidence. It is telling that the earliest written references to the prison trees only appeared in the 1910s, especially as the use of trees as chaining-posts is well established and recorded elsewhere in Australia. Early police stations in the Bush usually had no built structures outside of a canvas shelter, and it was common to chain prisoners to strong trees or heavy logs. This practice is known from official records and numerous newspaper accounts of the 19th century.

It does seem possible that the Wyndham and Derby boab trees were used as chaining-posts, and news articles of the 1930s and ‘40s mention this happening (although a huge chain would be needed to surround the tree). It is also quite possible that chains were affixed to a bolt in the tree. There is, however, no contemporary mention made of the inside of the tree being used, although the reminiscences of the Reverend Andrew Lennox – who lived in the region 1897-1907 – mention that the Wyndham boab had ‘a door… cut out of it, with a lock and key on it, the decayed pith cleaned out was used as a temporary locker by the police, ventilated by slightly porous ceiling’. This memoir was completed in 1958.

On the other hand, this 1894 article about the treatment of First Nations prisoners being marched to Derby makes no mention of the boab, and neither does this 1894 story about prisoners escaping from Wyndham lock-up. Even fairly descriptive articles about Derby and Wyndham in the 1900s make no mention of the prison trees (such as this one from 1905) and, more tellingly, neither does this very long 1907 article.

The boab is particularly conspicuous by its absence from a 1905 state government report on the appalling treatment of First Nations prisoners in the area, despite the report giving a very detailed and damning account of the gaols and the transportation of prisoners to Wyndham and other local towns. A stockman who appeared before this inquiry was questioned:

‘Have you seen natives being brought under escort by the police?’

‘Yes.’

‘Have you noticed whether the chains are attached to the constable’s saddle, or held in his hand?’

‘No. The chains were fastened round the blacks’ necks, and they marched along in front of the policeman’s horse’.

‘Are the women put in chains?’

‘Yes. This is done as a safeguard because they are witnesses against the male prisoners.’ (Western Mail, 25 February 1905)

A police constable also described transporting female witnesses:

‘How do you detain. them, with neck-chains?’

‘They are chained by the ankles.’

‘Do you mean that their two legs are chained together?’

‘No. I fasten the gin to a tree, with a handcuff and then fix the chain to one ankle with another handcuff – one handcuff, for each prisoner.’

‘Is it only at night that they are chained like this?’

‘It is necessary to detain them sometimes in the day when going through scrub or. rocky country, where they might get away; It is very rare that they have to be secured in the day time.’

(Western Mail, 25 February 1905)

While the non-mention of any boab in these reports doesn’t prove that the trees were not used as lockups, it does show that if they had, then the newspapers of the day would certainly have reported such things.

There is much doubt about the Derby tree in particular. The subject is explored in Gerald Wickens’ book The Baobabs* with the conclusion that there is zero official evidence for any use as a lockup, and that the tree is close enough to Derby (16km) that the police would have continued on to the town anyway (a gaol had been established there in 1887). Moreover, overland marches with prisoners tended to be long enough to cover several days and nights and as prisoners were chained together (by the neck) there was little need for makeshift lockups elsewhere, so why have one so close to Derby?

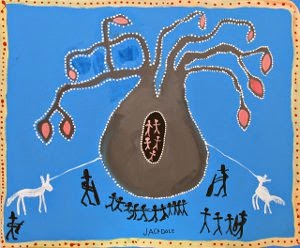

First Nations Perspectives

It is important to note that there are no Indigenous accounts of such a use. Researchers in Wyndham found that:

‘… the indigenous interviewees revealed alternate perspectives regarding the accepted historical wisdom of prison trees in the Kimberley. The tale commonly told is that Aboriginal prisoners were imprisoned within the hollow in the tree overnight on multi-day trips to take them to the nearest Kimberley gaol. Aboriginal perspectives of the prison trees revealed the belief that prisoners were actually chained to the outside of the tree while their police custodians slept in the dry hollow (away from monsoonal rains and mosquitos).’

Boabs feature extensively in First Nations social, material and spiritual culture. As a Department of Environment and Heritage report on the Kimberleys noted:

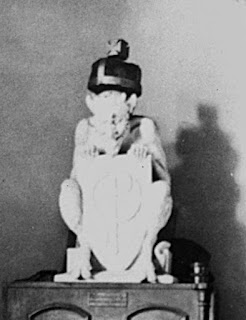

‘Some trees are believed to harbour extremely severe and potent powers, like Jilapur, a boab on the outskirts of Derby, more commonly known as the Derby Prison Tree. This tree is believed to be about 1,500 years old, and it has an opening into its hollow trunk large enough for a man to enter. There is speculation that prisoners were locked inside, and other accounts recall prisoners being chained around the outside of the tree. This tree is also a camping place for the Nyikina Creation Being Woonynoomboo.’

It was a practice in many First Nations cultures to place the bodies of their deceased on tree platforms and later put the bones inside trees or other concealed places. Confining living people inside trees that had been used in this way would have been unspeakably horrific from an Indigenous viewpoint. An account written in the 1910s noted the presence of human bones in the Derby tree:

‘It has even been suggested that the Derby tree was used by Aborigines as a resting place for the dead. The natives have long been in the habit of making use of this lusus naturae as a habitation; it is indeed a dry and comfortable hut. Some bleached human bones were lying upon the floor, which suggested that the tribe had also made use of the tree for disposing of the dead. A frontal bone of a skull clearly bore evidence that the individual had fallen a victim to the bullet of a rifle.’#

Such a use was also mentioned by author Ernestine Hill in 1934:

‘At Mayall’s Well, outside Derby, there is a tree-vault 25 feet in diameter, a native burying-ground from which they have taken the skeletons of a whole dynasty.’

Who ‘they’ were and why they took the skeletons is not elaborated on. Mayall’s Well is very close to the prison boab. Also writing in 1934, author Ion Idriess claimed that the tree hollow was ‘littered with aboriginal bones’ and that a ‘fragmentary skeleton’ was still there but word was that ‘sightseers from the irregular steamers had souvenired others’.

In 1999 the ‘Boab Prison Tree also known as Kunamudj’ was registered under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972. It is recognized as a ceremonial and mythological site associated with Kunamudj, the shark. The tree was also fenced off and a sign placed there reads thus:

‘Site of Significance

The significance of the Prison Boab Tree derives from its reputed use as a rest point for police and escorted Aboriginal prisoners en-route to Derby, and principally, its prior but less publicly known connection with Aboriginal traditional religious beliefs.

The Prison Boab Tree attracts many visitors. The fence was erected out of respect for the religious significance of the Prison Boab Tree and to prevent pedestrian traffic from compacting the soil around its roots.

The site is protected under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972. Please be advised that unauthorized entry beyond the perimeter fence is prohibited.

Note that snakes are known to inhabit the tree.’

The Verdict?

Widespread repetition of sensational stories without recourse to historical research is a key factor in urban myth-making. Newspapers and websites have certainly spread it far and wide over the last century, but these situations are always made worse when businesses have a vested interest in propagating myths. The tourist industry has to exploit whatever local resources/attractions it can to promote itself, and in this case the local industry around Derby and Wyndham certainly feature the prison trees prominently in their marketing.

From the dozens of ‘prison tree’ references on the Internet it would be very easy for a non-skeptical person to assume they must be true. Despite this, there seems to be little evidential basis for the lockup stories. There is none for the Derby tree, and only the writings of Rev. Andrew Lennox provide any eyewitness reference to the Wyndham tree as a lockup. It is quite likely that the trees could have been used for chaining people to, but not actually being confined inside. The stories have all the appearance of an urban (or in this case, rural) myth. What is more, this would be a myth that overshadows a much more interesting Indigenous perspective on the trees. Still, as the heritage-listings point out, their reputation as ‘prison trees’ does act as a useful reminder of the historical treatment of First Nations prisoners.

All that being said, if any reader out there knows of any direct evidence that these boabs actually were used as prison trees, I’d love to hear it.

* Full title: ‘The Baobabs: Pachycauls of Africa, Madagascar and Australia:’

# Herbert Basedow, ‘Narrative of an expedition of exploration in North-Western Australia’, Transactions of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, South Australia Branch, vol. XVIII, session 1916–1917, pp. 105–295.